A recent study aimed to explore the evidence surrounding ITB syndrome, in terms of pathology and management.

We reviewed this study in the latest issue of our Research Reviews – where industry experts break down the most recent and clinically relevant studies, for immediate application in the clinic.

STUDY TITLE: Iliotibial band pathology: synthesizing the available evidence for clinical progress – Geisler P (2020)

Study reviewed by Tom Goom in the March 2021 issue of the Research Reviews

Key points from the study

- Iliotibial band syndrome (ITBS) is thought to be a pathology of compression of sensitive structures, not friction.

- The ITB cannot be stretched and therefore treatment should not focus on stretching.

- Hip strength and control are thought to be key parts of management.

Background and Objective

ITBS is thought to be the most common cause of lateral knee pain, and yet it’s a pathology that is poorly understood and drastically under-researched! This narrative review sought to examine the literature to provide an overview of current thoughts on pathology and management.

Pathology

For some time, ITBS has been considered a ‘friction syndrome’ with the ITB thought to cause friction on the structures beneath it, leading to pain. More recent research however suggests that ITB pathology is more likely to involve compression of sensitive structures beneath the ITB rather than friction. This distinction is important as it has influenced treatment which has been targeted at stretching the ITB (to reduce friction) and steroid injections to reduce inflammation (e.g. in the bursa).

You can’t stretch the ITB!

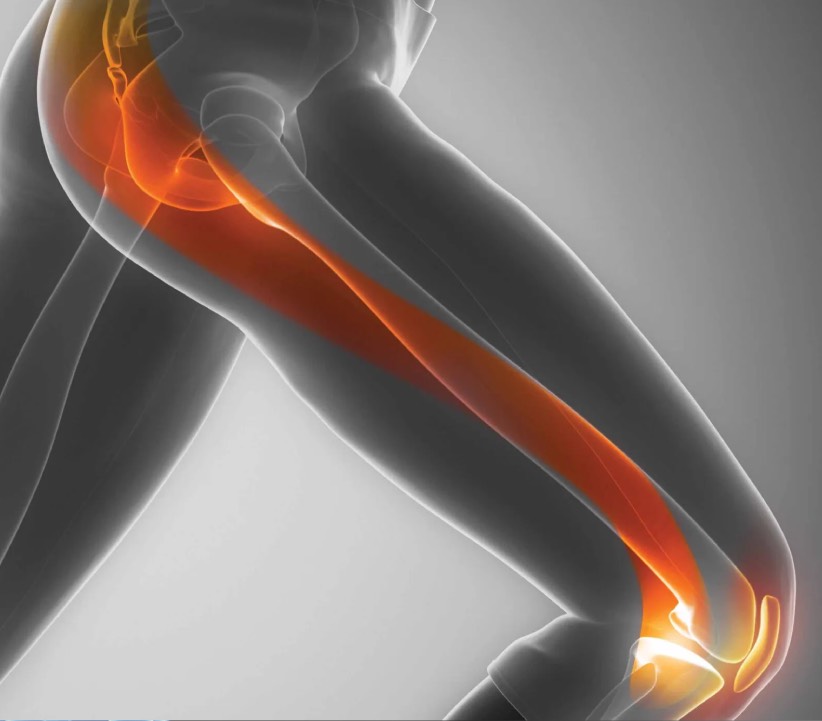

The ITB is a strong, complex structure with multiple attachments along the femur and distally around the knee. It provides stability for both the hip and knee joints and is thought to store and release energy like a spring. Current thinking is that a) you can’t stretch it; and b) you wouldn’t want to anyway!

Rehab Options

Loss of strength and control around the hip are thought to be key in the development of ITBS, especially weakness in hip abduction and external rotation, and increased hip adduction during loading (e.g. running). Training error is also thought to be a factor in over 60% of cases.

Treatment should aim to first calm symptoms and then address causative factors. The author suggests a progressive, 3-level programme:

- Level 1 – Low load, mostly open chain exercises (such as side-lying abductions, side-lying external rotations, and hip extension strengthening e.g. glute bridges)

- Level 2 – Moderate load, closed chain exercises (such as mini-squats, lunges, and step ups)

- Level 3 – Higher load exercises, including impact and sport preparation (such as goblet squats, single leg squats, and plyometrics)

Limitations

Narrative reviews can provide a useful overview of current thinking, however we must acknowledge the lack of high-quality clinical trials demonstrating the effectiveness of the recommended approaches.

Clinical Implications

This paper helps develop our understanding of pathology and treatment options for ITBS and may challenge common approaches such as stretching and massage. The principles of progressive rehab and addressing potential causes should be adapted to suit individual needs.

In patients with excessive hip adduction during running or a very narrow stride width, we may focus more on gait retraining with cues to address this. Our treatment should also include a graded return to goal activities based on symptoms. Initially we may need to reduce or modify more provocative training types such as downhill running or longer run durations before gradually re-introducing them as symptoms allow.

Much of the literature is focussed on biomechanical issues leading to overload of the ITB, however psychosocial factors must be considered too, especially beliefs about the injury and pain, as well as unhelpful training beliefs.